Evidence Atlas Review: POCUS for Viral Pneumonia

Written by: Sarah Banks MD, Jaclyn Walker MD, Matthew Riscinti, MD

Edited by: Michael Macias, MD, Paul Khalil, MD, Amanda Toney, MD

Introduction

The presentation of COVID-19 can vary from minimally symptomatic patients with mild viral syndromes to fulminant pneumonias with rapidly progressive hypoxemic respiratory failure. Many patients would benefit from early diagnosis leading to early quarantine, contact tracing, and close surveillance. This may lead to improved patient outcomes and prevent the spread of the disease. At this time, the diagnosis of COVID-19 has been extremely limited by the lack of access to testing and poor sensitivities of the viral nasal swab PCR assay, which has varied from 60-80% across studies (1) . Chest x-ray (CXR) findings may also lag behind symptoms when compared to other modalities including CT scan and point-of-care lung ultrasound. We sought to review the role of lung ultrasound (LUS) in previous pandemics and the evaluation of other viral pneumonias to help extrapolate its utility in the diagnosis of COVID-19. The majority of high quality studies came from the H1N1 influenza pandemic and seasonal bronchiolitis.

Ultrasound Findings in COVID-19

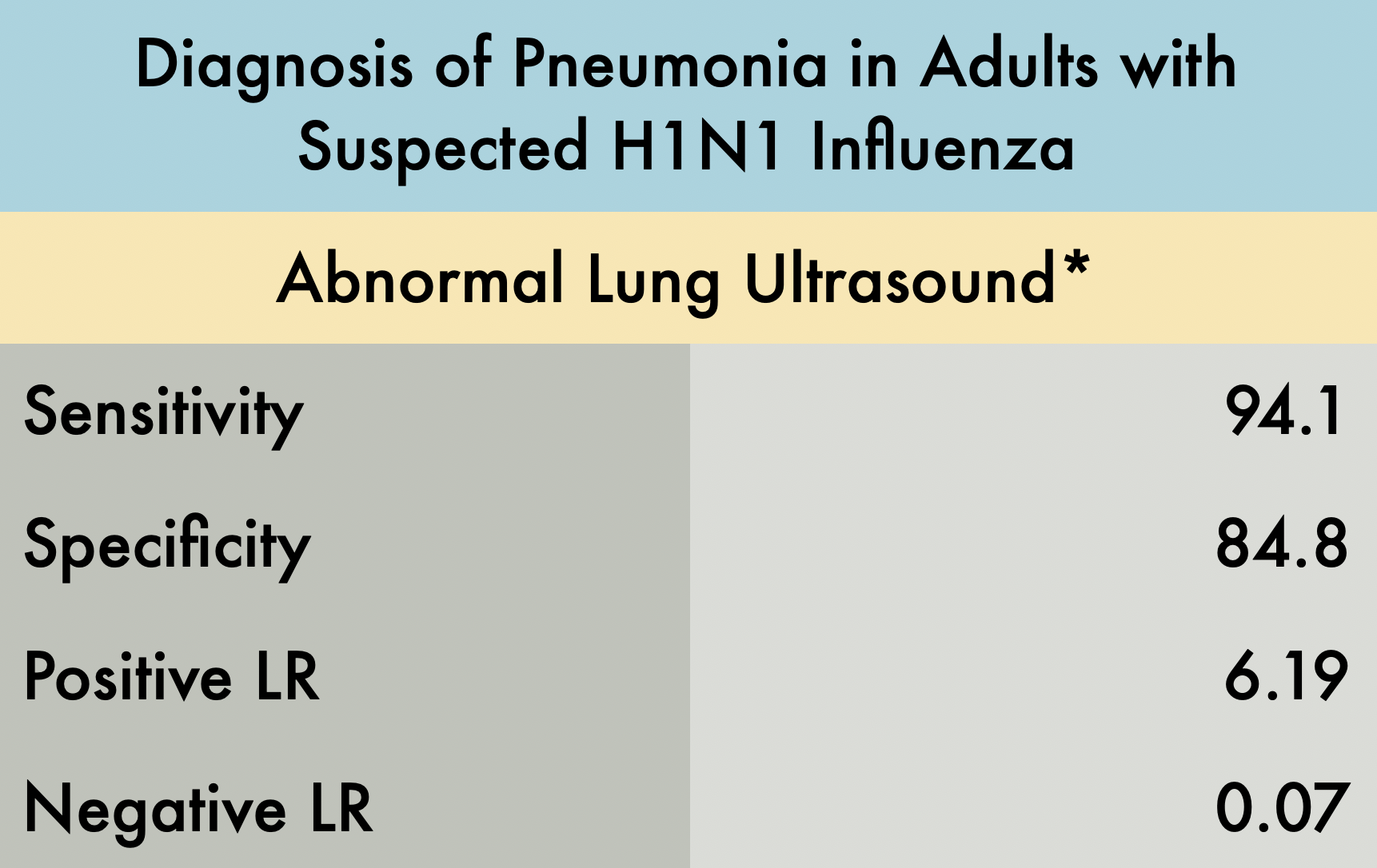

Paper 1: Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Adults with Suspected H1N1 Influenza

This was a prospective observational study comparing the operating characteristics of emergency department (ED) performed LUS versus CXR for the diagnosis of pneumonia in patients with suspected H1N1 influenza. The operating characteristics described in the table include patients with any pneumonia: primary bacterial pneumonia, viral (H1N1) pneumonia, or a secondary bacterial pneumonia in H1N1 infected patients. Patients were included in the experimental arm if they had signs or symptoms of influenza-like illness (ILI) with suspicion of lung involvement (pneumonia), either bacterial or viral. A total of 87 patients were enrolled in the study, 41 with ILI with suspected pneumonia and 46 with ILI without suspected pneumonia (control group).

The gold standard final diagnosis of pneumonia was based on the chart review of the hospital course including the history, physical exam, lab results, and radiographic findings. The reviewers were blinded to the LUS results. Three outcomes were reported: viral pneumonia with laboratory confirmation of the H1N1, primary bacterial pneumonia, or secondary bacterial pneumonia with confirmed H1N1.

The LUS studies were performed by three different emergency physicians with greater than 10 years of ultrasound experience. This study evaluated each hemithorax in five areas: two anterior, two lateral, and one posterior. The presence of any of the following signs on LUS indicated an abnormal exam*:

>3 B-lines per intercostal space

Thickness of pleural line > 2mm or coarse appearance

Consolidation or hepatization

Pleural effusion

Lung ultrasound showed a sensitivity of 94.1% and specificity of 84.8%. An abnormal ultrasound was present in 32 of 34 patients with the ultimate diagnosis of pneumonia (including viral and bacterial). In patients with initially negative CXRs, 15/16 demonstrated an US pattern reflecting interstitial syndrome, all of whom ultimately had the diagnosis of pneumonia. In patients with initial abnormal CXRs, 17/18 had positive chest ultrasounds. The control arm did have 5/33 false positives which the author speculates may have been attributed to subclinical viral infections without clinical relevance or previous interstitial syndromes reflecting prior illness. The one false negative case was a patient with bacterial pneumonia with a deep, perihilar opacity.

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size and that the LUS studies were performed by expert sonographers. Beyond this though, we recognize that this study identified operating characteristics of LUS for all pneumonia and did not specifically analyze the sensitivity and specificity of lung ultrasound for viral pneumonia alone. It also excluded patients with comorbidities making this a very limited patient population which likely greatly affected the specificity of POCUS for pneumonia in this setting. Furthermore, expert adjudication was used to determine final diagnosis which is an imperfect gold standard. In the end, H1N1 has many similar characteristics to the COVID pandemic and this study is highly suggestive that lung ultrasound, particularly in patients with negative CXRs, can assist in diagnosis.

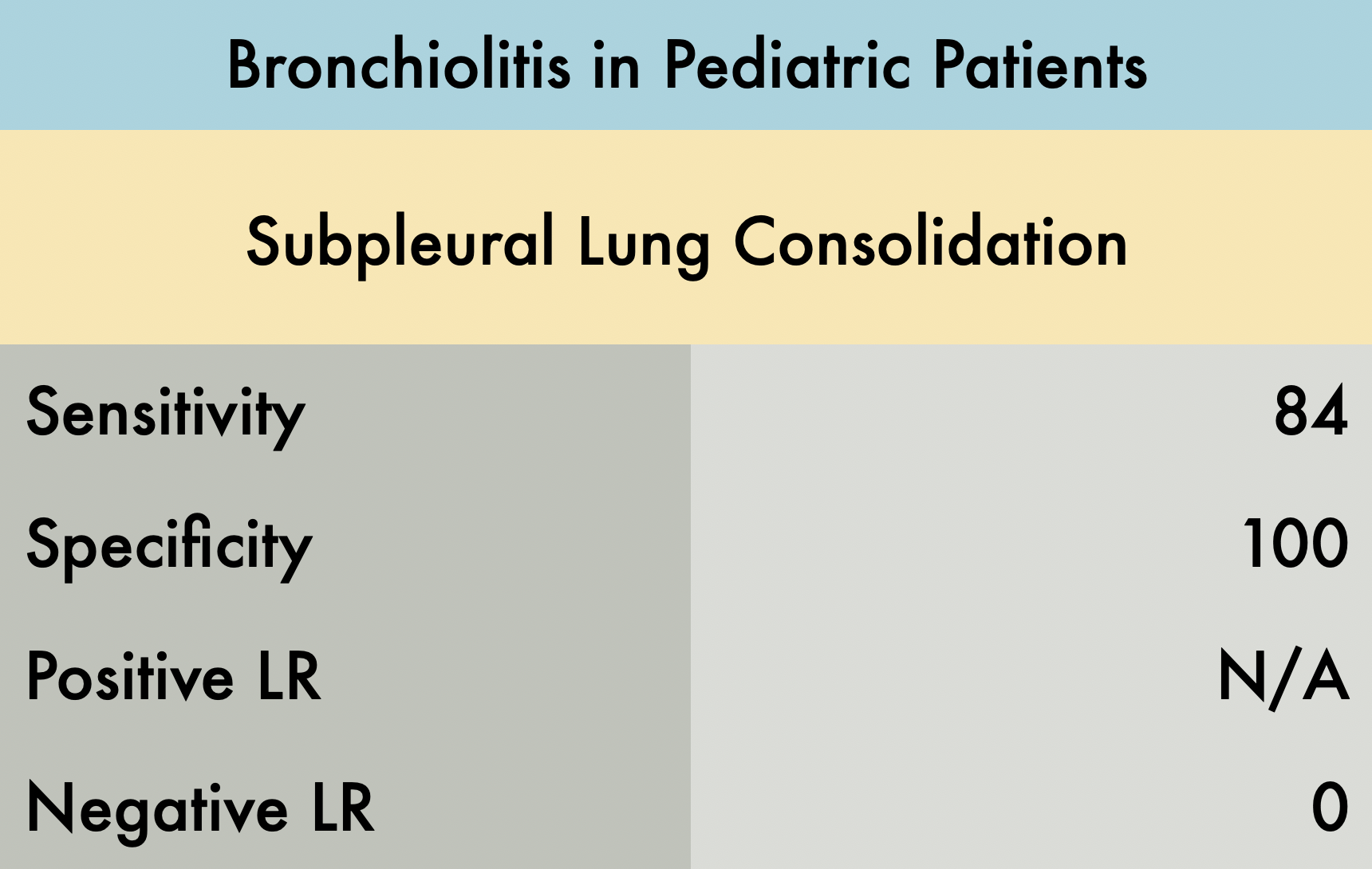

Paper 2: Bronchiolitis & POCUS

This was a prospective observational study comparing the operating characteristics of emergency department (ED) performed LUS versus CXR for diagnosis of children with bronchiolitis. A total of 52 patients were enrolled in the study. All LUS were performed by one blinded experienced sonographer. Abnormal LUS findings in the study included: subpleural consolidations, b-lines (confluent b-lines or areas of multiple b-lines), and pleural abnormalities. In 44/52 infants with bronchiolitis, subpleural consolidations were present, compared to 0/52 infants without bronchiolitis. Notably, the sensitivity increased from 84% to 90% when all LUS abnormalities are considered (b-lines and pleural irregularities in addition to subpleural consolidation). The presence of multiple areas of lung consolidation and confluent b-lines (white lung) were most predictive of the bronchiolitis severity. CXR was considered positive in 38/52 patients when lung consolidation, peribronchial thickening, or hyperexpansion was identified. Nine patients with a negative CXR but abnormal LUS findings had a clinical course that was consistent with bronchiolitis.

An advantage of LUS in this study was decreased time to diagnosis. LUS was interpreted during the study, while CXR took an average of 4 hours and 45 minutes to interpret after imaging was obtained. Limitations of this study include the small sample size and a single operator for all ultrasounds performed. Bronchiolitis is typically a clinical diagnosis and as such was defined by history and clinical examination in this study. The current study compared LUS to CXR, but there is no gold standard for diagnosing bronchiolitis. In fact, the AAP AAP recommends not performing CXR when considering the diagnosis of bronchiolitis (4) and is more commonly used to rule out other diagnoses. Further studies are needed to determine whether LUS may be a better imaging test to assist in diagnosing bronchiolitis and distinguish bronchiolitis from other pulmonary pathologies such as bacterial PNA. These limitations make the specificity of 100% questionable and indicate the need for larger studies.

Learn More About POCUS in COVID-19 on our COVID-19 Page

COVID-19 Ultrasound Card

Denver Health and The POCUS Atlas have teamed up to create a COVID-19 Ultrasound protocol. These will be printed on plastic and will distributed to providers. This is FOAMED: Click to download a PDF version or contact Matthew Riscinti, MD for an Adobe Illustrator source file if you want to adapt this for your own institution. Our cleaning protocol is also available at that link.

We believe that collaboration and human-centered design will tackle the biggest problems in healthcare. The contributors to the card include, in no particular order: Matthew Riscinti, MD, Michael Macias, MD, Tim Scheel, DO, Paul Khalil, MD, Amanda Toney, MD, Molly Thiessen, MD, and John Kendall, MD.

References:

Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens JAMA. 2020;

Testa A, Soldati G, Copetti R, Giannuzzi R, Portale G, Gentiloni-Silveri N. Early recognition of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia by chest ultrasound. Crit Care. 2012;16(1):R30. Published 2012 Feb 17. doi:10.1186/cc11201

Caiulo VA, Gargani L, Caiulo S, et al. Lung ultrasound in bronchiolitis: comparison with chest X-ray. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(11):1427–1433. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1461-2

Silver AH, Nazif JM. Bronchiolitis Pediatrics in Review. 2019; 40(11):568-576.